For many years, ‘greening’ a building was an effective reputation booster. Now, it’s becoming an imperative and real estate investors need to kickstart their pathway to zero carbon if they want to avoid a ‘brown discount’.

Today, stakeholders across all sectors of the economy are paying particular attention to the sustainable development of their businesses. This is especially true of the real estate industry, which accounts for 39% of energy-related CO₂ emissions globally. Thanks to an increased focus on Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) criteria, for renters and landlords alike, ‘doing nothing’ means the value of their asset will likely be impacted by changing market expectations and regulations related to sustainability.

The goal to achieve carbon neutrality across Europe by 2050

During COP21, 195 countries signed the Paris Agreement to limit global warming to below 2°C, ideally 1.5°C, compared to pre-industrial levels. As for the real estate sector in Europe, all buildings – new and existing – should be carbon neutral across their whole lifecycle by 2050. According to the Paris Agreement, the role of the financial sector in financing the transition to a low-carbon economy is crucial. Furthermore, reflecting the European Union’s commitment to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) and the EU Taxonomy Regulation (EUT) are cornerstones of the EU’s Sustainable Finance Strategy and aim to help European economic actors reach net zero. Regulations, in line with existing European law, are also implemented at a national level, as is the case with the Energy-Climate law in France. A tightening of regulations has contributed to a decline in interest in non-performing assets, increasing the risk of stranded assets. The concept of stranded assets, in the context of real estate, refers to properties that will not meet future energy efficiency standards and market expectations as part of the transition to net zero, and might therefore be exposed to the risk of early economic obsolescence. Moreover, 80% of buildings that will be in use in 2050 have already been built today. Therefore, decarbonizing the real estate sector means improving the performance of existing assets.

See also: The rise of ESG: the evolution of environmental regulations in Europe

Growth of the Green Premium market

For years, the real estate industry has been focusing on “green premium”, with the first signs of the impact of decarbonization efforts on the real estate market being observed as a result of this. Green buildings are properties that achieve or exceed sustainability requirements, for example properties built to high energy standards. These properties were subject to a rent or market price premium in some markets. In fact, according to a study published in the International Journal of Sustainable Built Environment in 2017, green-labelled buildings do involve capital costs, however they achieve a higher financial return, both in rent and sale price, than conventional buildings. The study found that the BREEAM certification resulted in premiums of 22.1% and 14.7% on rent and sale prices respectively, compared to non-certified buildings in the same neighbourhood in the UK. As for LEED-certified buildings, they saw premiums of 7.8% on rental prices and 9% on sale prices. Certification schemes and labels are the easiest way to assess environmental performance in this context. Certifications from a reputable energy performance scheme, such as BREEAM, LEED or other voluntary labels provide data and evidence to the market. This allows the transactions to be based on a more precise overview of sustainability performance.

Building certifications drive value creation

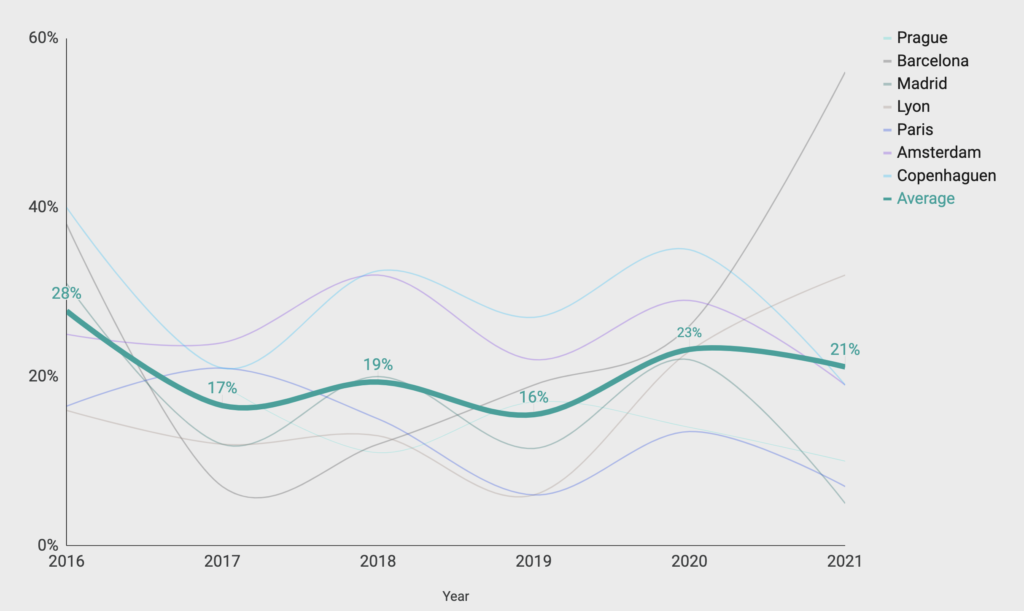

The positive effects of green certifications and labels on the value of the buildings and properties are confirmed by other studies. CBRE (Commercial Real Estate Services), a global leader in commercial real estate services and investments, released a new study in 2021, which focuses on the relationship between sustainability certifications and rental prices. The study highlights how sustainability office certifications impact value creation. It was conducted on dwellings from 15 cities across 12 European countries and based on the effect of 5 certifications (BREEAM, LEED, DGNB, HQE, WELL).

Figure 1: Certified rent (premium) compared to uncertified rent (2016 – H1 2021)

Across all the cities analyzed, this graph shows that certified buildings have an average rent premium of between 13% and 29% over five years, depending on the market, and a rental price that is 21% higher than the market average. This illustrates how certified buildings achieve a higher rental price compared to similar, non-certified properties. It indicates a considerable risk of ‘brown discounting’ for properties with a relatively weak sustainability performance.

Poor energy performance in buildings could compromise your investment value

The effect of green buildings on the rest of the existing building stock, the vast majority of which is neither sustainable nor energy efficient, is evident. So-called ‘brown buildings’, which are buildings with poor energy ratings, decreased in value relative to the mean. Today, brown buildings are far more common than green buildings. Around 75% of the EU’s building stock is not energy efficient. Older or outdated buildings that clearly show evidence of obsolescence or deferred maintenance pose a real economic risk for industry investors, and may require additional capital outlay for improvements. In the long run, properties with poor energy ratings will face higher operating, insurance and maintenance costs. These properties represent depreciative assets, whereas newly constructed or renovated ones that meet or exceed requirements represent an appreciative asset. More importantly, buildings which perform poorly and don’t meet market expectations in the future could face weak demand, higher vacancy rates, lower rental growth and falling rental prices, leading to quicker economical obsolescence and ultimately becoming ‘stranded assets’.

Where does the market stand ?

We are already witnessing the shift. Brown discounting is becoming more and more noticeable in today’s European markets. Consequently, the green premium is fast becoming a less significant topic. Owners of existing brown properties face two concerns: a lower rental price while they are still under management and eventually the loss of its selling value on the market, damaging the overall portfolio.

Figure 2: Green Premium vs. Brown Discount. Source: Runde & Thoyre (2010)

The green property market is expanding. Demand for green buildings is greater than demand for brown properties. It means that tenants prefer green space and this factor is sufficient for tenants to choose between green and brown. According to the graph, this is a long-established concept that is gradually coming to fruition: green premium is the new normal, and brown buildings are gradually being left by the wayside.

From Green Premium to Brown Discounting

Until now, the focus has been on labels and certifications for individual buildings, which are becoming more well-known over time. Today, the implementation of new European and national standards provides guidelines to be followed by the entire market. The standards will no longer be voluntary but regulatory. Real estate players are faced with increasingly strict regulations. For example, the SFDR regulation requires European real estate investors to provide greater transparency across their portfolios. Therefore, expectations regarding energy efficiency are changing; some features – triple glazing, efficient cooling systems, etc. – which improve energy efficiency, are beginning to be regarded as standard. Buildings that fall short of these new expectations will see a fall in value which may lead to brown discounting. Therefore, high energy performance is now being considered as the new ‘normal’. For this reason, we are seeing a strong correlation between higher valuation and better performance.

More and more countries are starting to make the changes necessary to achieve net zero emissions in the coming decades. Building owners will also face increasing pressure to be more transparent and to implement changes to achieve these targets. Portfolios including carbon-intensive assets risk diminishing in value. On one hand, this threat is due to increasingly stringent regulations, on the other, from pressure from financial institutions, stakeholders, and occupiers. So far, there have been few attempts and studies to quantify how big the impact of brown discounting might be, but this trend only stands to accelerate, and asset managers who do not address it are at risk of finding themselves with stranded assets, damaging their portfolio’s overall value and struggling with upcoming regulations such as the SFDR.